Dash Shaw’s animated fantasy film (no relation to the NFT game that turns up persistently in web searches on the title) is an interesting experience. It’s quite trippy, which is both appropriate and intentional—it’s set in the Sixties, and the zoo is located near San Francisco. Its themes are relevant to the world of 2024: the ethics of zoos, the amorality of late-stage capitalism, the fraught relationship between humans and the natural world. It’s an explicit response to both Jurassic Park and the sanitized utopia of Disney World’s EPCOT Center. I think I detect a dark homage to Peter S. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn, too, with echoes of Mommy Fortuna and her Midnight Carnival (“Creatures of Night, Brought to Light”).

Cryptids are very much a part of Shaw’s world. The question its protagonists must answer is whether to leave cryptids alone and let them remain hidden but vulnerable, or try to preserve them in a protected location—in a word, a zoo—and share them with the public.

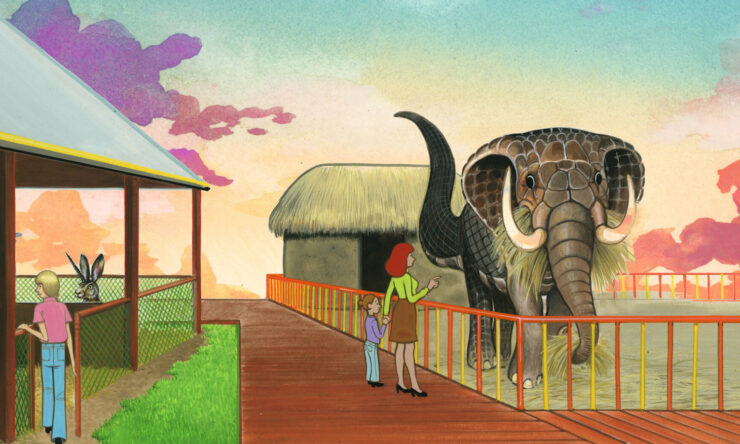

Elderly, wealthy Joan has big dreams and plenty of land to devote to them. She lives in a medieval-zoid tower surrounded by a fence many feet high, which encloses a combination zoo and theme park, complete with gift shop and Disneyesqye attractions. Younger but equally dedicated veterinarian and cryptozoologist Loren Grey travels the world in search of cryptids, but the main focus of her search is one in particular, the Baku.

The Baku is a Japanese chimera or hybrid creature, part pig, part elephant, part sparkly flower child. She feeds on dreams, sucks them out of sleepers’ heads and leaves them in peace. When Lauren was fourteen, the Baku relieved her of a lifetime of prophetic nightmares. Lauren has been searching for her ever since.

That’s the main story, but the film begins with a crucial subplot—and it’s immediately clear that this cartoon is not for kids. Flower children Amber and Matthew are wandering through the woods under a canopy hallucinatory stars, grooving on nature and each other. They strip (but he keeps his socks on) and engage in explicit sex.

In the aftermath, Matthew explores further and finds his path blocked by a fence. The fence is strong and high, and Matthew climbs it. Amber is less adventurous, but eventually follows him up and over, into a pastoral landscape of grass and trees surrounding a tower.

And there, grazing in the grass, is a unicorn. She’s not the white goatlike creature of medieval (and Peter Beagle) lore, but a rather poorly conformed bay mare. With a horn.

Matthew can’t resist provoking her. Like tourists in Yellowstone who insist on trying to pet the fluffy cows, Matthew finds out the hard way that this is a wild creature. She is not tame, she is not gentle, and she has no compunction about using her lethally sharp horn.

Amber reacts with horror and then with rage, beats the unicorn to death and takes her horn.

At that point I had to decide whether to keep watching. I have never even seen The Godfather because of the horse’s head. This was way beyond my Nope Nuh-Uh zone.

Mind you, the opening credits hadn’t even rolled yet. But I had an article to write. I persevered.

I’m not sorry I did, all things considered. There’s more explicit sex and more over-the-top violence, but there are some lovely moments as well. The characters, both human and cryptid, are nicely rounded and sometimes complex. Not all cryptids are “just” animals, and their form does not determine their level of sentience. Some of the least humanoid are the most intelligent.

There is an antagonist, of course, and of course he’s an evil cryptid hunter allied with evil government forces. He stalks Lauren as she hunts the Baku, and does his best to capture and exploit her cryptid allies. Gustav the Faun, who first appears in a sort of XXX-rated Siberian Narnia, plays both sides. Phoebe the Gorgon, who is engaged to marry a human, is a loyal ally of Lauren and Joan, and a clear example of how some cryptids may hide among humans. Pliny, one of the Blemmyes (headless men with its face in its torso), shows us both how Lauren collects cryptids, and how human caretakers exploit their charges. He’s very young, but he also makes a choice, and it’s not an easy one.

The zookeepers’ story dominates the film after the opening credits, but Amber and the unicorn horn have a crucial role to play in the final conflict. Along the way we meet a wide range of cryptids from all over the world. Some are dangerously aggressive and not very intelligent—they just attack whatever comes at them—and others are at least as capable of higher brain functions as humans. Vaughn the swamp creature is Joan’s significant other. The shimmering rainbow Pegasus (“that gay horse,” says the evil cryptid hunter, slightly anachronistically) fights bravely for the zookeepers. The Baku doesn’t speak, but is remarkably expressive, and she doesn’t seem to feed randomly. She appears to choose whose dreams she will consume.

The message here, among the rest, is that cryptids are people, too. They have their own lives and thoughts and feelings, and their own agenda. Joan and Lauren collect them with the best of intentions, meaning to both protect them and share them with the human world.

In the end, that’s no better or worse for them than evil Nicholas’ plan to sell the cryptids he captures to the highest bidder. Joan envisions a peaceable kingdom full of happy creatures entertaining flocks of human visitors (but with the more dangerous or aggressive cryptids confined to various enclosures and cages). Nicholas dreams of weaponized monsters waging war on the nations of the earth. Neither of them asks the cryptids how, or where, they want to live.

Amber the not so random naked flower child more or less inadvertently resolves the issue. She answers the zookeepers’ question, and gives Nicholas and his army what they deserve.

In the process, we learn where cryptids and mythological beasts have been hidden through all of human history. We see what Amber and Matthew see in the prologue, and we finally understand what it means. It’s a satisfactory ending, if not an easy or a universally happy one.